bad naturalist 1 .webp.webp

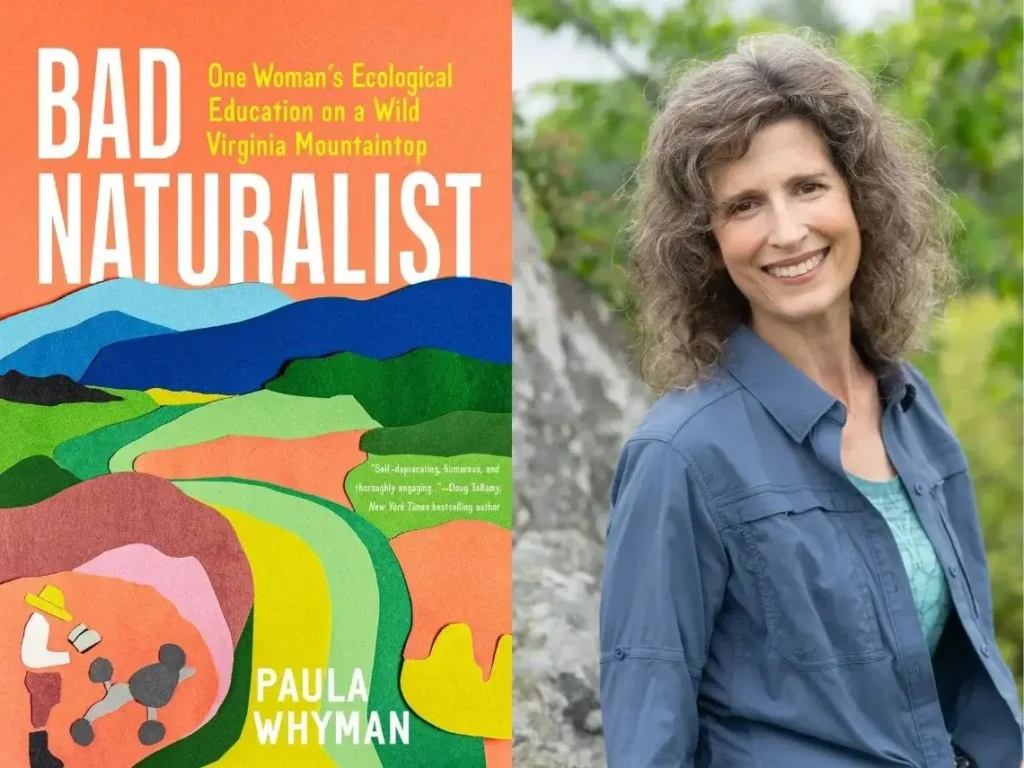

Years ago, author Paula Whyman left her DC-area home in search of a rural spot, hoping to get back to nature. What she found was 200 acres of old farmland atop a Virginia mountain. Despite having little experience in gardening or conservation, Whyman put down roots on the mountain top, and chronicled her efforts in her new book Bad Naturalist.

The following passages are excerpted from Bad Naturalist, and have been lightly edited for length.

Wherever people go, they reshape the land, and on this mountain it’s no different. Two hundred years ago, many of these hillsides were timbered for orchards. Around forty years ago, most of the orchards were replaced with cattle pasture. In the past decade, farmers stopped grazing cattle on the mountain. Haying eventually stopped, and mowing stopped, too. For a while now the land has been subject to its own rules; once people stopped managing it, it began to reshape itself. An old pasture filled in with blackberry. The forest encroached on the meadow, pioneer poplar, locust, and sassafras saplings taking the lead. A hayfield filled with hardy natives—and with weeds. Invasive shrubs climbed up and over a hillside, relentlessly expanding their range. Rather than a typical farm, the mountaintop looks unkempt, uninhabited, overgrown. The tendency might be to leave such a place alone—if humans stop interfering, nature will do what nature does, and take over. The land didn’t need me; it would rewild itself—right? Not exactly. Once a place has been disturbed by humans, the only way to repair it is to keep disturbing it, but in the right way. The tricky part is figuring out what that means.

****

In the Southeast, grasslands have declined by 90 percent. In Virginia, where this stunning, scraggly mountaintop is located, the Piedmont prairie, the native grassland community that once dominated the region east of the Blue Ridge mountains, is considered extinct; only small remnants hidden in tiny pockets around the state survive. With those numbers in mind, you can begin to understand why conservation of privately owned forests and grasslands is critical.

Back in 1962, even before MacArthur and Wilson had published The Theory of Island Biogeography, an independent researcher named Frank Preston declared that “it is not possible to preserve in a state or national park a complete replica on a small scale of the fauna and flora of a much larger area.” Parks alone can’t begin to help us ward off the worst effects of climate change, human development, the influx of invasive species, and other pressures that endanger biodiversity. Even if we put all the public lands together—all the national, state, and local parks and nature preserves—without the participation of private landowners, our parks would end up becoming species museums showcasing a handful of plants and animals, those lucky enough to survive the isolation.

Standing on the mountain, with all those acres of rolling hills unfolding in front of me, my goal to plant a small patch of meadow seemed timid. This land was big—I should think bigger! What if I could return this mountaintop to its natural glory? It would serve as a living example of how to restore native meadows! Pollinators would come from all around! I pictured sheep grazing on one of the hillsides. Just a handful of sheep. I’d make sheep-milk cheese. (I can’t eat dairy. I was clearly losing my mind.) I’d put up a fence to protect the sheep from the coyotes and bobcats and bears. Better make that an electric fence. Already I was taming the wilderness.

Even as I dreamed up a Percy-Shelleyesque vision of myself communing with nature, skipping through meadows, bluebirds winging around my head, I was hit with second thoughts. I had the nagging sense that I might be glossing over a few important factors (besides poison ivy and rattlesnakes). Like, at this stage in my life, and considering my various physical limitations, did I really want to take on such a big, ambitious project with an open-ended timeline and a learning curve as steep as one of those hills?

I understood, in theory, that caring for land was a major commitment— I would soon understand it even better in practice. To complicate matters, not only was there no house to live in up here, not even a shed for storing tools, there was no power, and no working well. This land would require time, sweat, single-mindedness: your basic obsession. In other words, exactly my jam.

So I chose to try to restore these two hundred acres, to attempt to transform ailing fields into native meadows, and a barren forest floor into a teeming native understory. Even though, outside of the knowledge I’d gleaned from books like Wilding and “weed warrior” expeditions with my kids along the Potomac River, I had no real idea what would be involved in doing this work on a vast mountaintop, or what the end point of such a project would look like—much less whether a true end point was possible.

If this course of action seems hopeful, foolish, and delusional, that’s the wheel around which my feelings about it cycle, sometimes in a single day. My frustrating limitations aside, what I do have going for me is a tendency to become preoccupied with a topic, studying it and talking about it nonstop (much to the irritation of my family). At various points in my life, I’d done this with mangrove trees, gray whales, carpenter bees, rats, sea urchins, carpet beetles, lizards, and flying squirrels. The mountain was not only a subject, but a place I could dive into and lose myself, a source of fascinating and unlimited information to fill my brain and give me a sense of purpose. And unlike most of the places that inspired those other fixations, the mountain wasn’t a place I would only visit—it would actually be my home. I’d literally live with the outcome, the success or failure of my endeavors. I didn’t know yet how that would feel or how it would influence my decisions.

My belief that I can revitalize this place has an almost magical quality to it, as if, as the land grows healthier, I’ll grow stronger, too. This may be magical thinking, but it’s also an exercise in hope. Standing on top of the mountain, contemplating the idea of somehow bringing change to this formidable landscape, is a dizzying experience. Whatever happens, like the wildflower seeds that stick to my trousers, the land grabs hold of me, and it won’t let go.

Taken from Bad Naturalist© Copyright 2025 by Paula Whyman. Published by Timber Press, Portland, OR. Used by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Source link

2025-01-30 09:09:51

Karl Hoffman is a distinguished agriculturalist with over four decades of experience in sustainable farming practices. He holds a Ph.D. in Agronomy from Cornell University and has made significant contributions as a professor at Iowa State University. Hoffman’s groundbreaking research on integrated pest management and soil health has revolutionized modern agriculture. As a respected farm journalist, his column “Field Notes with Karl Hoffman” and his blog “The Modern Farmer” provide insightful, practical advice to a global audience. Hoffman’s work with the USDA and the United Nations FAO has enhanced food security worldwide. His awards include the USDA’s Distinguished Service Award and the World Food Prize, reflecting his profound impact on agriculture and sustainability.