(This article was originally published on Forbes on January 26, 2022)

For more than two years, human society has been dealing with ramifications of the Covid-19 pandemic and that already feels like a long journey. It has killed millions, caused significant human stress, and precipitated economic disruption. Unfortunately the timeline for its resolution is unclear. For the past seventeen years, the Florida citrus industry has been grappling with a pandemic of its own – in this case an exotic bacterial disease that plagues the trees grown to produce the popular and health promoting fruit and juices we enjoy (oranges, grapefruits, lemons, limes, tangerines…). This severe plant disease now occurs in all 45 citrus producing counties in Florida. The disease was first described in China in the early 1900s where it called Huanglongbing or “yellow dragon disease.” In the U.S. it is usually called “HLB” or “Citrus greening.”

|

| Asian Citrus Psyllid Adult (image USDA-APHIS) |

In 1998 an insect called the Asian Citrus Psyllid (ACP) showed up in Florida and caused concern because it was known to vector this disease while feeding on the tree’s sap. However the bacteria didn’t get introduced into the state for a while, and it was not until 2005 that the first diseased trees were found. In the ensuing years the insect and disease spread to essentially all of the citrus groves in Florida where they threaten the very survival of this important industry ($6.7 billion total economic impact, 33,000 jobs, $1.816 billion at the farm level). However, both pests are also now present in other US citrus growing states and represent a looming threat to those industries.

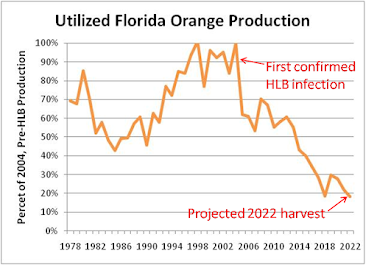

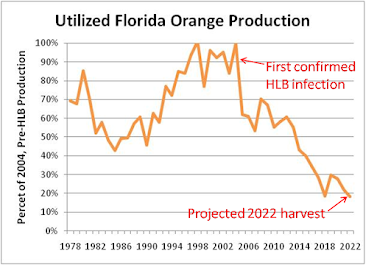

This story has been unfolding slowly over these many years. The reason such a long-running problem has returned to the news of late is that the USDA published a depressingly dark production estimate for the 2022 Florida orange crop. They project that it will be down to 44.5 million 90-pound boxes – only 18% of the crop seen in 2004 – prior to the HLB era (see graph below)

|

| Ever since HLB appeared in 2005, production has been dropping (graph by author based on USDA-NASS data) |

How Low Can It Go?

In Florida, this disease is causing considerable concern about the future. Once the bacteria have been introduced into the tree by the ACP insect, they become systemic. The infection leads to a 50-70% decline in tree root function, reduced tree vigor, fruit drop, and problems with fruit ripening. Infected groves generate lower and lower marketable crop yields over time. That financial strain has induced around 5,000 farmers to quit growing citrus altogether. Unfortunately the potential to shift to different crops (e.g. blueberries, strawberries, peaches, vegetables) is limited because of weather and competition from other US growing areas and from imports. Citrus used to be the most profitable option in South Florida and that is why it was grown on around 900,000 acres prior to HLB. The declining yield and acreage trends for oranges can be seen in the graphs below.

|

| Orange production has dropped both because of reduce acreage and because of declining yield per acre. This has also been true for other citrus types (Graphs by author based on USDA-NASS data) |

Particularly for the juice industry, critical mass is required for running processing plants. Therefore it has been necessary for the major brands to include imports from Mexico and Brazil. The one grower-cooperative juice brand that continued making a “100% Florida-grown” product for many years (Florida’s Natural) has no longer been able to maintain that distinction.

So Is There Any Hope?

As is often the case in agriculture – adversity has inspired a diversified, private/public research effort to identify and/or develop pest management options for this disease and its vector. Funding for this comes from the industry itself (eg. The Florida Citrus Research and Development Foundation), the state ( University of Florida/IFAS), the federal government (USDA) and private technology companies. In 2018 the National Academy of Science published a 287 page review of the research effort with inputs or reviews from 23 scientists. One of the key conclusions was that no single solution would be likely to solve this problem and that a diversified strategy was needed. The following is at least a partial list of the strategies that are being pursued for both immediate and long-term solutions to this challenge.

Nutrition and water management – because HLB compromises the tree’s root system, it becomes more important than ever to provide nutrients via fertilizers. However, this is a challenge in the extremely sandy Florida soils because these minerals can be washed down below the rooting zone to become a potential groundwater issue. The state’s extension experts recommend “spoon feeding” of small doses of fertilizer at multiple times during the year delivered through the irrigation systems which are now used in virtually all the groves. Major additions of organic matter are also used at replanting and/or in later years, but it is a challenge to retain their effects in these soils. Overall, growers are advised to follow BMPs (best management practices) that do as much as possible to reduce the effects of HLB while also protecting the environment.

CUPS – One fairly extreme but near-term option for growers who are planting new citrus stands is to use a system called CUPS –“Citrus Under Protective Screening.” The idea is to completely exclude the ACP vector by growing the trees under a protective 40-50 mesh high density polyethylene screen.

|

| There is an orange grove under this protective cover designed to completely exclude the insect vector of HLB (Arnold W. Schumann, University of Florida/IFAS) |

This sort of structure costs around $1/square foot and the screen has to be replaced every 7-10 years. That capital investment can theoretically make sense because in addition to avoiding HLB damage, the trees begin to bear fruit within 2.5 years of planting vs the normal 5-7 year range. Still, economic analysis of this system suggests that it is only feasible for the “highest possible yield of premium-quality fresh fruit with a high market price” and that only with a high degree of market stability.

Breeding New Citrus Varieties – there are several, long-running University and USDA breeding programs for citrus which have added HLB resistance to their goals in addition to other kinds of pest resistance, yield and quality traits, and consumer traits like easy-to-peel tangerines. There are some promising examples of new varieties coming out of these programs. There is also another ambitious inter-species hybridization effort working with a citrus relative called Poncirus trifoliata or “Japanese Bitter Orange.” That source of genetic diversity may provide “constitutive disease resistance (CDR) genes” in hybrids that can then be back-crossed to restore fruit and juice quality. Modern technologies like genome resequencing and transcriptome sequencing are used to speed-up this process. Poncirus hybrids are also being evaluated for relative resistance to the vector insect, ACP.

Rootstock Breeding – with tree and vine crops there are usually independent breeding efforts for the part of the plant that grows above ground (scion) and that which grows below (rootstock). Researchers at both the University of Florida and the USDA have long-standing rootstock development programs that were seeking to address other disease and nutrition issues before HLB, but they have found a few of their hybrids to be promising for reduced impact from infections. In some cases they have observed reduced proliferation of the pathogen inside the tree. There is the possibility that this sort of bacterial growth reduction effect will move up to the grafted scions where the fruit is formed. They are also breeding for “dwarfing” rootstocks that enable early bearing, “ultra-high density” plantings suitable for machine harvesting – a potentially more economically viable option for the future.

Biocontrol – pest management involving live biological control agents is an increasingly important part of the tool box for farmers in general. Researchers at the University of Florida’s research and education center in Apopka have been testing a benign strain of a different bacterial pathogen of grapes called Xylella. By injecting this organism into HLB infected trees it appears to be possible to delay the development of severe symptoms and thus keep the orchard producing longer. This option is not yet available to growers because it will require EPA registration, but research continues to determine how effective the protection could be for new trees and how often new injections may be needed.

Genome Editing – The recent advances in genome editing technologies such as CRISPR are generating excitement for many applications ranging from human health care to agriculture. An extensive review of how this might be applied to counteract HLB has been published by Chinese researchers in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences. While the USDA and other global regulatory agencies have signaled that they will minimize barriers to this approach, it remains to be seen how the EU will respond to broad scientific support for a smooth regulatory path for this kind of technology. If instead, the EU follows its historic tendency to employ extreme precaution regardless of scientific advice, their influence on export markets will negatively impact this future option for Florida and other citrus growing regions. In any case, this solution will not be available soon because it takes several years to get from a gene edited cell to a tree that is old enough to generate buds for grafting on to rootstocks.

Genetic Engineering: like many other brand-sensitive food industry players, the Florida orange and grapefruit juice producers have acquiesced to the pressure to display the insidious “Non-GMO” label even though there are no commercial “GMO” cultivars being grown. There was an excellent article written in 2013 about the early history of this pandemic and the concern that growers would be denied any transgenic tools with which to fight HLB.

There is an active genetic engineering research program being pursued by a multi-party team involving Texas A&M, The University of Florida, Southern Gardens Citrus, Purdue University, the University of California and the USDA. It involves identifying genes for antimicrobial peptides to counteract the HLB organism and then either getting those expressed in the trees or delivering them with the help of a benign version of a common citrus virus. In the later case the trees themselves would not be “GMO” and it would be possible to use the technology across many existing and new varieties. There are regulatory processes involved (USDA, EPA) but those are nearing completion. Even if the “conventional breeding” options are promising and less controversial, it is always logical to have a diversified strategy – especially for a perennial crop which needs solutions that will remain effective over something like the 20-30 year lifespan of a new planting. That National Academy of Sciences review from 2018 specifically recommended “expanded efforts in educational outreach to growers, processors, and consumers” about the topic of biotech options. Back to the Covid-19 pandemic analogy, disinformation abounds when it comes to both vaccines and “GMOs.”

Conclusions

So yes, the continuing HLB pandemic will result in a record low Florida orange crop in 2022. But there is still reason to hope that a combination of grower dedication and research to develop diverse strategies will ultimately mean that consumers can continue to enjoy these flavorful and health-promoting fruit and juice options. Finding solutions is not just important for the Sunshine State but also for other HLB-threatened states like Texas, Arizona and California.